- Dividend investors often make the mistake of adding dividends onto earnings when evaluating a stock, inflating the value of the business.

- Dividends come out of earnings, so adding dividends onto earnings double-counts earnings and inflates the value of the business.

- Investors should focus on the future earnings and how much they are paying for each dollar of earnings, rather than adding dividends onto earnings.

Introduction

During my eight years of writing about stock investing it has been commonplace for me to run across investors, usually dividend investors, who make the mistake of assuming dividends are paid out to investors in addition to earnings. I recently discovered the source of this misunderstanding and I’m going to share why investors shouldn’t add dividends onto earnings when evaluating a stock, and also why I think so many dividend investors make this mistake.

The Mistake: Adding Dividends To Earnings

Usually I see this mistake take two common forms. The first is that I will share a valuation for a stock based on the future earnings of the business relative to the price the market is charging investors for those future earnings, and in the comment section someone will ask “What about the dividends?” I have literally been asked some form of this question dozens and dozens of times over the years. And, while there are occasionally some nuances we can get into, which I covered in my article “The Four Cases When Dividends Matter“. But most of the time, especially when quality dividend stocks are trading at nosebleed levels as most are today, dividends don’t matter if an investor is performing a good earnings analysis, and in that article, I examine the exceptions to that general rule.

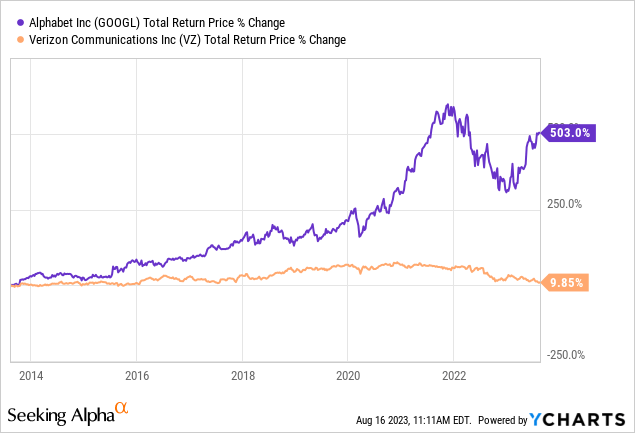

The reason dividends don’t matter is because dividends come out of earnings. This means that if you value a business based on its likely future earnings, and then you add dividends on top of that, you are double-counting earnings and inflating the value of the business. This is very simple at its core. If a business earns $10 per share and has that $10 sitting in its bank account, and the shareholder has $0 in their bank account. If the business pays $5 per share out to shareholders, then the business now only has $5 in its bank account and the shareholder has $5 in their bank account. It still adds up to $10 in earnings. This is how dividends work in their basic form. So if you add the $5 dividend payment to the $10 in earnings when performing a valuation of the business, then you are treating the business as if it earned $15 per share, when it only earned $10 per share. If an investor does this, not only are they inflating the value of the actual business and probably therefore paying too much for the stock, they are also giving an advantage to businesses that pay out higher portions of their earnings power in the form of dividends. This results, all other things being equal, in dividend investors willing to pay far more attention to a stock like Verizon (VZ

We can see the difference in the 10 year returns in this example, which is actually pretty accurate in relation to how big of a mistake this valuation error really is. (If you don’t think Google is a good comparison here, Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A

The second form I often see this mistake emerge is when trying to estimate the future returns of a stock, investors will use a formula something like: Earnings Growth + Dividend Yield = Future Stock Total Return. The reasoning here is a business that has earnings growing at a 10% rate which pays a 4% dividend can be expected to have a stock price return over time of 14%. This makes a similar, but slightly different error. It conflates the business earnings with the stock price, or assumes that whatever the current valuation of the stock is, P/E ratio-wise, will be maintained over time. This can be a serious error as well because what the market is willing to pay for each dollar of earnings over time can vary a lot.

The key to avoiding this error is to always understand that stocks are a partial ownership of a business. And what investors should mostly care about when buying a business is how much earnings they would likely collect from the business over time and how much they are paying for each dollar of earnings. If an investor buys a stock with a 5% earnings yield (20 P/E), for every $100 they invest, the business will earn $5 per year. And if earnings are expected to grow 10% per year, that $5 they can collect in earnings will grow 10% each year. (So in year 2 they would collect $5.50 in earnings from the business.) But, if an investor buys the stock of a business with a 10% earnings yield (10 P/E) for that same $100 per share, they will earn $10 per share the first year, and if earnings grow 10% per year, then they will have $10 per year growing at 10%. (So in year 2 they would earn $11.00 per share.) As we already discussed in the last section, the dividend yield is irrelevant because whatever the business pays out in dividends, it loses in earnings it gets to keep. The formula of Earnings Growth + Dividend Yield = Future Returns does not distinguish between $5 growing at 10% and $10 growing at 10%, and it then makes of the further mistake of adding dividends on top of that. So, the stock of a business priced at $100 per share earning $5 per share, which pays out a $4 dividend (4% dividend yield) with earnings growing 10%, would be assumed to return 14% annual returns over time, while the stock of a business priced at $100 earning $10 per year growing at 10% which doesn’t pay a dividend would be expected to grow at 10% over time and would appear less valuable, when the truth is it’s twice as valuable.

These are not small mistakes, and my experience over the years interacting with investors is that they are reasonably common mistakes.

What Is Causing The Confusion?

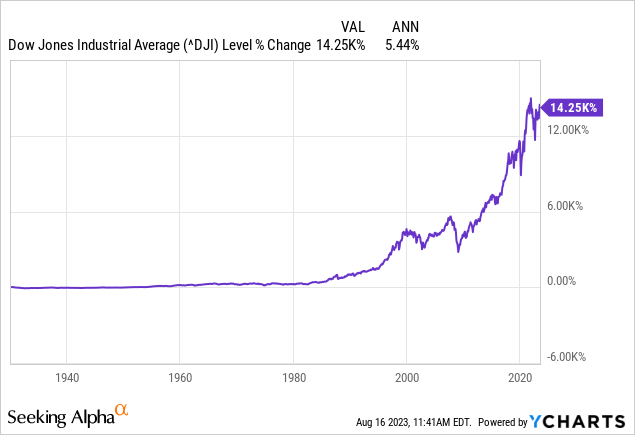

The primary cause of the confusion is rooted in not understanding the difference between a business and a stock, and the returns from a business’s earnings and the price of the stock. This comes from investors using historical stock price returns from indices to show potential future returns. The formula for doing this is Stock Price (or Indices Level growth) + Dividends = Total Return.

The chart of the Dow Jones Industrial Average Index (

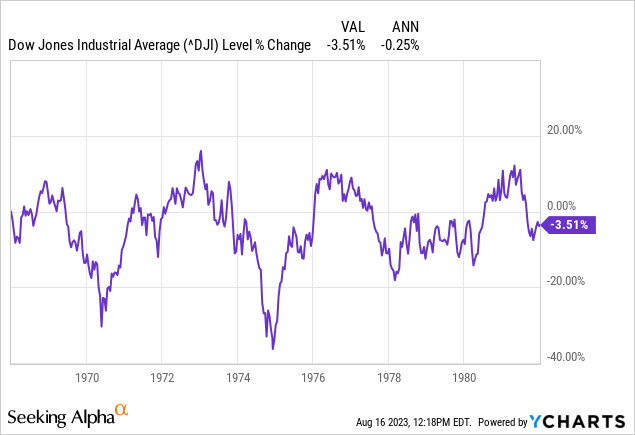

For example, look at the returns of the Dow Jones Industrial Index from 1968 to 1982.

This was a period where the index went from a very high valuation in 1968 to a very low valuation in 1982. The annual return over this 14-year period was flat, but I can assure you, even though I don’t have earnings data handy for this period, earnings grew substantially for the index’s businesses. So, this was a period where earnings growth and price growth did not correlate. The reason for that is primarily because the starting earnings yield in 1968 was very low (high P/E ratio), and therefore didn’t produce the owners of these businesses who bought them in the late 1960s very much money going forward in the form of actual earnings.

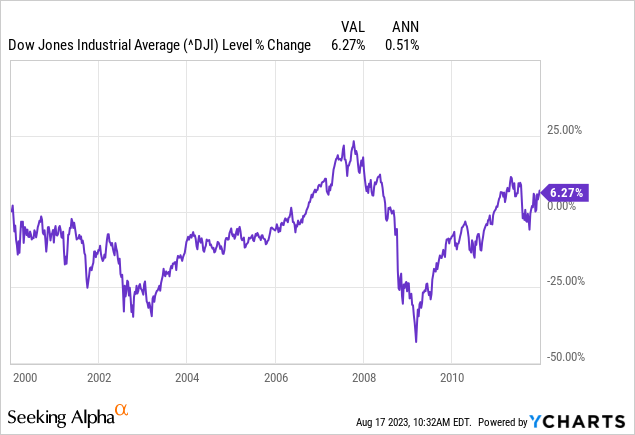

We see a similar pattern over the 12 years from 2000 to 2012 where the Dow had a flat return.

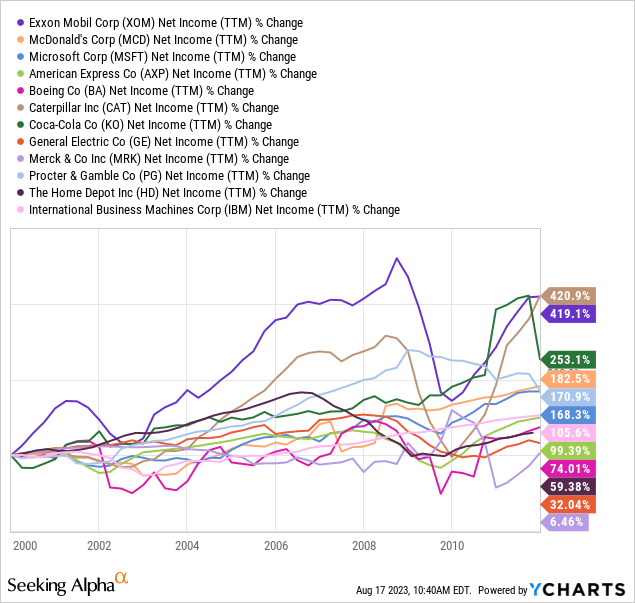

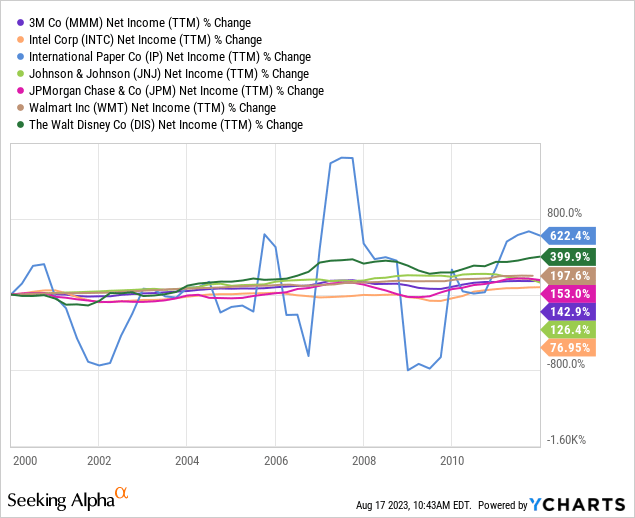

Below is a sampling of the earnings growth that took place from some of the Dow components from 2000-2012.

There were a few Dow businesses that went bankrupt or had transformative M&A during this period that aren’t included above, but the earnings growth of the vast majority of Dow components during this time was more than 100%, while the index was flat. This shows that earnings growth alone, when combined with a dividend, is not a good way to estimate future long-term returns from any given point in time.

Conclusion

In the end, estimating the future earnings of a business requires investors to at a minimum consider the stock price, the current earnings per share, and the expected earnings growth over a specific period of time. The longer an investor can go forward in time with correctly forecasted earnings, the more accurate their estimation of the future stock price will be because earnings collected over time by the business and stock price growth correlation tend to increase over time. However, the farther out in time we go, like 10, 15, 20, or 30 years, the more difficult it becomes to accurately estimate where earnings will be. So, I usually limit my valuation time period to about 10 years, which isn’t extremely long, but long enough that the correlation between collected earnings (via the earnings yield and earnings growth) is typically pretty close to the stock price change.

But when we are evaluating the actual business as an owner of a business would evaluate it, the vast majority of the time, as long as earnings are growing at a reasonable rate (above inflation), then dividends don’t matter at all in my opinion, and they certainly shouldn’t be added on to an earnings valuation. Really, the only time a person should add in dividends to something in my view is if they are looking at the historical returns of indices, but in that case, they aren’t really performing a valuation analysis of a business, they are looking at stock prices and dividends, which are connected, but very different than examining the potential returns of a business.

Photo by Francisco De Legarreta C. on Unsplash