Crazy People is a 1990 American comedy starring Dudley Moore and Daryl Hannah. Moore plays advertising executive Emory Leeson, who experiences a nervous breakdown. This causes him to design a series of “truthful” advertisements that are blunt and bawdy. One of Leeson’s more memorable campaigns is for Volvos, which includes the tagline: Volvo — they’re boxy but they’re good.

Dividend-paying stocks are like the Volvos of the investing world. They’re not fancy or exciting, nor do they produce windfall profits over the short term. However, they have a lot going for them when you take a deeper look under the hood.

Let’s look at the historical performance of dividend-paying stocks, including the conditions under which they have tended to outperform their non-dividend paying counterparts, as well as whether the current market environment is supportive of future outperformance.

A caveat to the Volvo analogy

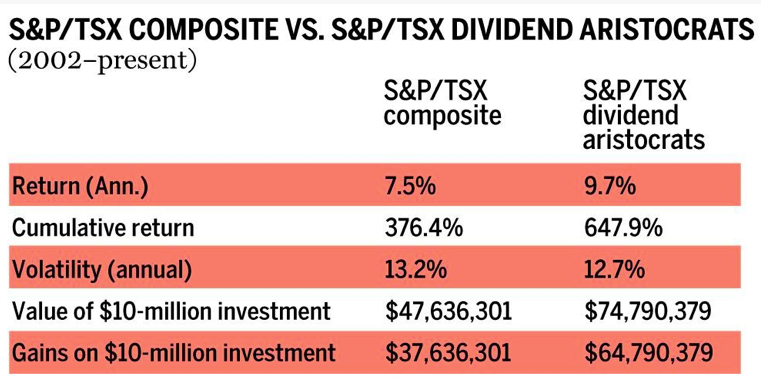

The Volvo tagline mentioned above implies a clear trade-off: the suggestion being that one needs to sacrifice performance for reliability. But the historical data implies this has not been the case with dividend-paying stocks. They have exhibited greater stability than their non-dividend paying counterparts and produced higher returns, thereby providing investors with a “have your cake and eat it too” proposition.

Since 2002, the S&P/TSX dividend aristocrats index has produced an annualized total return of 9.7 per cent versus 7.5 per cent for the S&P/TSX composite index

Nice to have in strong markets

Dividends have historically been an integral part of equity market returns. Going back to 1990, 52.2 per cent of the S&P 500 index’s total return can be attributed to the power of compounding reinvested dividends. On a relative basis, Canadian dividends have been even more prominent than in the U.S., with reinvested dividends responsible for an astounding 63.3 per cent of the composite index’s total returns.

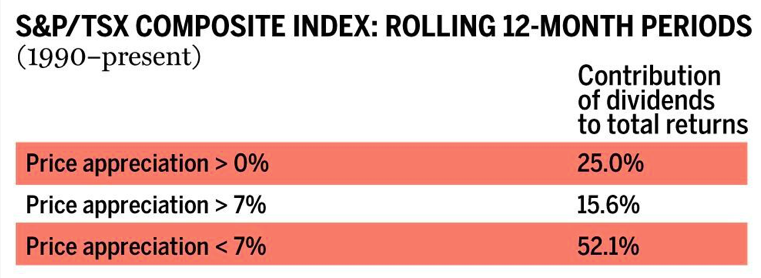

Although dividend contributions to total market returns have been substantial over the past several decades, this contribution has tended to substantially vary over shorter sub-periods. As the accompanying table shows, dividends tend to play a smaller role in times of strong price appreciation. By contrast, dividends play a far more substantial role during periods when capital gains have been muted.

The relative importance of dividends has also varied with capital gains. In all rolling 12-month periods since 1990 in which the composite index experienced price appreciation, dividends were on average responsible for 25 per cent of total returns. In those periods when prices rose by more than seven per cent, dividends’ share of total returns was only 15.6 per cent, compared to 52.1 per cent when prices rose between zero and seven per cent.

It goes without saying that when prices fall, dividends have been of paramount importance for the simple reason that they’re the only things equity investors have going for them.

There when you need them most

Memories become short when non-dividend-paying growth stocks deliver outsized gains, and it becomes tempting to ignore the benefits of equity income. More recently, stupendous gains in the megacap Magnificent 7 growth stocks (Tesla Inc., Apple Inc., Nvidia Corp., Amazon.com Inc., Microsoft Corp., Meta Platforms Inc. and Alphabet Inc.) make dividend-paying stocks seem like quaint artifacts from an earlier time.

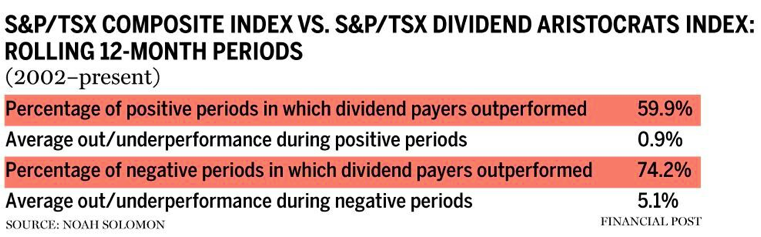

However, dividends still constitute the most stable component of overall equity returns. A company’s dividend-payout ratio (the percentage of earnings paid out as a dividend) is generally more stable than its share price. As a result, dividends are not subject to the same fluctuations as stock prices. On a related note, dividend-paying stocks tend to outperform in challenging market environments.

The S&P/TSX composite index has produced positive results in 75.1 per cent of all rolling 12-month periods since 2001. During these instances, the dividend aristocrats index outperformed the composite 59.9 per cent of the time, with an average outperformance of 0.9 per cent. The relative performance of dividend-paying stocks has been far more impressive in declining markets, with the dividend aristocrats outperforming the composite 74.2 per cent of the time and by an average of 5.1 per cent.

Where we stand today

Following the global financial crisis of 2008, central banks the world over dropped rates to zero and then kept them below the level of inflation for the next 13 years. They also poured fuel on the fire by adding more liquidity through various non-conventional easing measures, including quantitative easing.

Although these measures were unprecedented, they nonetheless pale in comparison to the amount of stimulus injected into the veins of the global economy in response to COVID-19. The one-two punch of fiscal stimulus and near-free money served as rocket fuel for the resulting multiple expansion and above-average stock returns.

Today, central banks find themselves in a “once burned, twice shy” predicament. The United States Federal Reserve failed to act when inflation began to accelerate in 2021, claiming the problem was “transitory.” This miscalculation placed its credibility under increased scrutiny and has served as a stark reminder that highly stimulative policies can ignite inflation.

The upshot is that monetary authorities are unlikely to adopt the type of stimulative policies that characterized the 2009-2021 period any time soon. As a result, markets will likely have to adjust to a less friendly environment for the foreseeable future. This eventuality, combined with the spectre of slowing growth and heightened volatility means investors should embrace the importance of dividends.

Photo by Hector Bermudez on Unsplash